Pachuco: A Conversation of The Americas

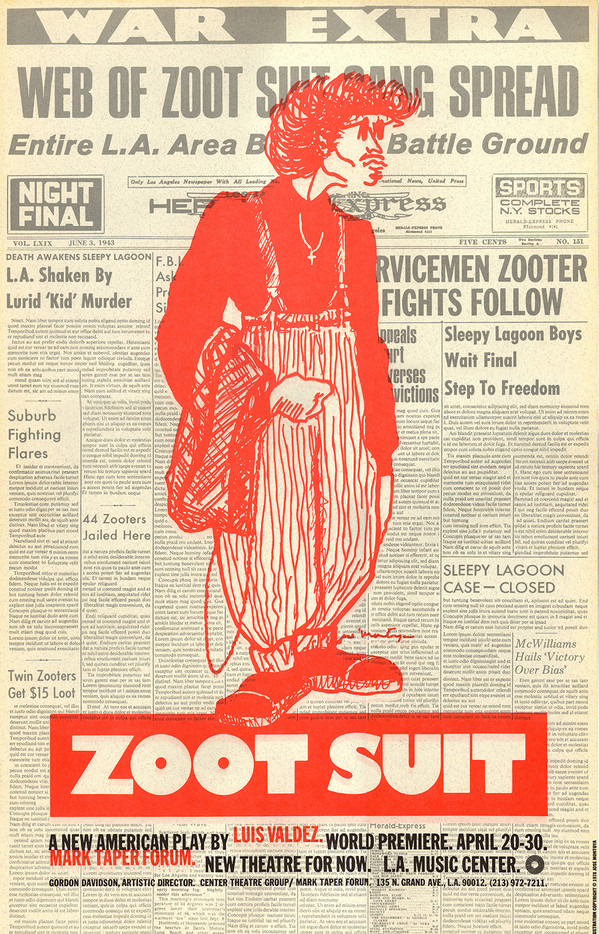

In honor of our revival of Zoot Suit, Richard Montoya of Culture Clash shared with us his reflections on the pachuco and what this play means to him. His father, the pachuco poet and artist José Montoya, was a close friend of Luis Valdez and designed the art that was used in the first Center Theatre Group New Theatre for Now production.

Webster’s Dictionary now describes pachuco with all the economy of a José Montoya etching. That the word exists there in the “P” section of the bible of English definitions is a testament to a dedicated dramatist, poets, songwriters, and novelists. Chief among them is Luis Valdez, who along with Lalo Guerrero, Raul Salinas, Montoya, and the titan of Mexican writers, Octavio Paz, all played key roles in this star turn for a single word and its inclusion on the bookshelves of nearly every teaching institution in the Americas. No small feat, and perhaps just as important and remarkable is the dialogue that proceeded the placement of the loaded word in this good book: an artistic conversation that spanned the better part of a century and moved up and down the Western Hemisphere like a literary shadow cloud specter ignoring all manner of walls and borders.

In the poem "Pachuco Portfolio," for example, Montoya dedicates his poem to his idol Mexican comic and an early innovator of pachucismo style and manner: "…Pa’ Tin Tan y la Tonya y su carnal Marcelo…" Tin Tan brought élan, humor, and comedic precision as sharp as the creases in his drapes to his nightclub act and films. With a sprinkling of Chicano-tinged caló in his speech, Tin Tan was resplendent and communicating in the finest zoot suits the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema could manufacture. Puro basilon. Puro pachuco el paisa!

Mexican-American kids of the late 1940s were soaking up the eternally cool Mexican comics like Resortes at Saturday matinee movie houses all over the Southwest where "Spanish" films were shown. Post-war American chavolos with shoeshine boxes ready to shine the calcos of their older pachuco brothers and uncles, many of whom returning home from The War, where they served with uncommon valor and honors. These pioneering pachucos left indelible impressions on the young minds of a generation that literally looked up to and followed them.

- Noun 1. Pachuco

- A Mexican-American teenager who belongs to a neighborhood gang and who dresses in showy clothes.

Though we may quibble with Webster’s un-flowery definition, I urge you instead to read a poem by Raul Salinas, a pachuco/pinto/poeta who tripped through the complexities of barrio streets and jails with graceful elegance.

Or consider the genius of Lalo Guerrero, who shone a bright ballroom light on our ability to sing, shout, and code switch all night long and in rhythm! Don Lalo bending his bolero guitar chords toward boogie-woogie and laying them at the doorstep of rhythm and blues while never forsaking his Barrio Viejo roots as he strode proudly alongside Cab Calloway.

Of Octavio Paz we read in Montoya’s pachuco elegy where he poetically challenges the Literary Lion of Mexico: “…Octavio Peace Brother didn’t get us into his Labyrinth and was made the nobler?" A reference to Paz’s monumental The Labyrinth of Solitude. That this literary pairing took decades to gestate and unfold is remarkable. Writers wrestling with the exact moment when Mexicans became Chicanos, it may be contested but most agree that the molecular moment happened at the border of El Paso, Texas, or better known as El Chuco! And the vatos certainly wore modified zoot suits with jazz-like improvisation but always with our own unique sense of rasquachismo. It is with no irony that the best tailors of the region in those times resided across the Rio Grande in a place called Juarez, Mexico!

Who copied whom matters little in the final analysis. Like the origins of our entire history, it is complex. Akin to uncoiling the riddle of who created film noir: was it Bogart's smile staring down a barrel of a gun, the fog of London, or the moment French existentialist writer Jean Paul Sartre stepped off a plane in the New York mist turning up his collar and pulling down his fedora? (Which Bogart immediately copied.)

The Old Poets would be happy to know that we’re back on the mainstage and finally into an elusive "Labyrinth." Valdez’s landmark revival is living, breathing, poetic proof of it. The tectonic plates of a hemisphere shift slightly as Mr. Bichir carries nearly a century of conversations on his broad pachuco shoulders. Don’t worry he can handle it ese! That’s part of the beauty and blue-collar barrio practicality of the zoot armor.

Before there was a divisive line we were one. Following the brutal and bloody winter of our presidential election, where nearly all who came from Mexico were vilified, now thanks to Valdez and crew we can delight in adding an important vocation that also journeyed north from south: one of Mexico’s finest actors. It makes perfect poetic sense. Prologue is epilogue and in the words of Cesar Chavez, who was also known to wear a zoot suit in his youth: "It doesn’t matter when you get there, only that you do get there…" Now we are there thanks to the ancestors and to the singular genius and tenacity of El Maestro Luis Valdez. Todos Somos Pachucos!

Related Articles

"Zoot Suit"

Luis Valdez brings his groundbreaking 1978 smash back to the Mark Taper Forum January 31 – April 2, 2017, to celebrate Center Theatre Group’s 50th Anniversary.

Buy Tickets