When Theatre Royalty Take On Real-World Royalty

Looking Back on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘The King and I,’ Then and Now

Playwright David Henry Hwang knows a thing or two about artistic tropes and stereotypes about Asians, a topic that several of his plays have thoughtfully grappled with. Yet Hwang admitted—in a conversation with Center Theatre Group Artistic Director Michael Ritchie—that The King and I still holds a special place in his heart. There’s this complicated feeling where I know it is kind of inauthentic and making a political point subtly,

he said, but it’s done so beautifully that by the end of it I’m still in tears.

Hwang’s experience watching the 2015 Broadway revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic musical was one of the major inspirations for his recent collaboration with Jeanine Tesori, Soft Power, onstage at the Ahmanson May 3 – June 10, 2018. Soft Power seeks to explore the trope of Westerners bringing their culture to a foreign land and teaching them to become more civilized/compassionate/like us by reversing the roles.

The King and I serves as excellent source material. The 1951 musical tells the story of Anna Leonowens, an English governess who travels to Siam (modern-day Thailand) in the 1860s to tutor the children of King Mongkut. Anna teaches the King and his children of the modern world and Western sensibilities, and Anna and King begin to fall in love. By the end, the dying King insists Anna continue to advise his son, who ends the play by making several decrees that push the country to be more Western.

Questions of authenticity and bias become more glaring when examining the historical source material. Though Anna Leonowens was a real-life figure who was employed by the King of Siam, the musical itself is based off a fictional novel inspired by Leonowen’s own memoirs, the accuracy and honesty of which has been disputed. One New York Times writer characterized the play as ultimately a confection built on a novel built on a fabrication.

Portrayed as a confident and capable yet somewhat naive ruler in the show, the actual King Mongkut was well-educated and a proponent of modernization. Many of the intellectual and social reforms made by the King and his son that Leonowens took credit for were either made before her arrival or are disputed as having been influenced by her in any significant way.

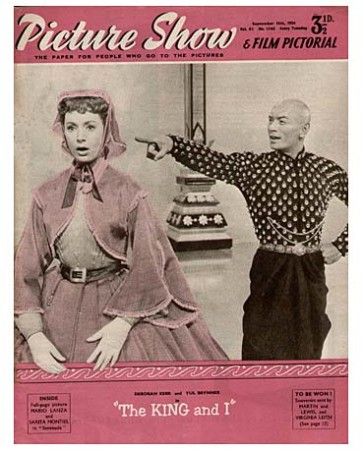

Because of these historical inaccuracies (among other reasons), the film and play were banned in Thailand in 1956, and a 1999 remake of the film was also banned. None of this mattered to most 20th-century American audiences, however. The original 1951 production ran for three years with over 1,200 performances, and won several Tony Awards including Best Musical. Numerous revivals over the next four decades stayed fairly true to the original, with actor Yul Brynner—who starred as the King in the original production—reprising his famous role across multiple productions for over 4,600 performances, as well as starring in the 1956 film adaptation for which he won an Academy Award.

Brynner and his overwhelming success have been seen by some as emblematic of the play’s triumphs and shortcomings. A Russian-born actor playing a Siamese king mimicked the plot’s insistence that Asians should become more like Westerners. The King and I is in no small part an exploration of how a Westerner’s influence enriches the lives of non-Westerners in a foreign land, all from a Western viewpoint.

Yet it would be unfair to label the play as fully antagonistic or dismissive toward Siamese culture. Rodgers and Hammerstein were fairly progressive for their time: Bartlett Sher, director of the 2015 revival production, noted that earlier drafts of the script contained questions about imperialism and capitalism, and the two creators pushed racial boundaries and promoted tolerance in later work such as in South Pacific (which has its own problems). Sher speculated that corporate and political pressure forced the duo to tone their more controversial messages down in The King and I.

Setting aside arguments over the play’s positive or negative intentions, some artists have made active efforts to tell a more well-rounded story. Christopher Renshaw—director of the 1996 Australian revival—visited Thailand in order to make a more authentic production both visually and thematically. Renshaw made a concerted effort to represent Thai culture as fully as the English culture of Anna: It's easier to weigh the notion of East meets West when you can believe in both sides,

he said.

However you judge the politics, cultural depictions, and bias of The King and I, underlying it all is a story of compassion and love. That (and the music) still elicits tears out of famous playwrights, and it’s what makes The King and I a classic well worth reimagining.