L.A. Writers’ Workshop

Turning the Page at Center Theatre Group

The L.A. Writers’ Workshop Festival will take place over two weekends in September at the Kirk Douglas Theatre. Since its inception in 2005, Center Theatre Group has fostered a cohort of playwrights to help them write new plays. For the first time in the history of the L.A. Writers’ Workshop, all ten playwrights from a single group will have their plays presented together, giving L.A. audiences a sneak peek of their work. This cohort of ten women have worked together over the past few months under the guidance of Associate Artistic Director Luis Alfaro to write ten plays. Learn more about these women and the stories they want to share at the upcoming festival.

“Los Angeles is filled with great possibilities and here, we find first, 10 examples of excellent craftspeople. They remind us that the future is female. They also represent the diverse communities of Los Angeles. We are humbled to welcome them into this institution, for this, is a writer’s theatre.” –Luis Alfaro, Associate Artistic Director.

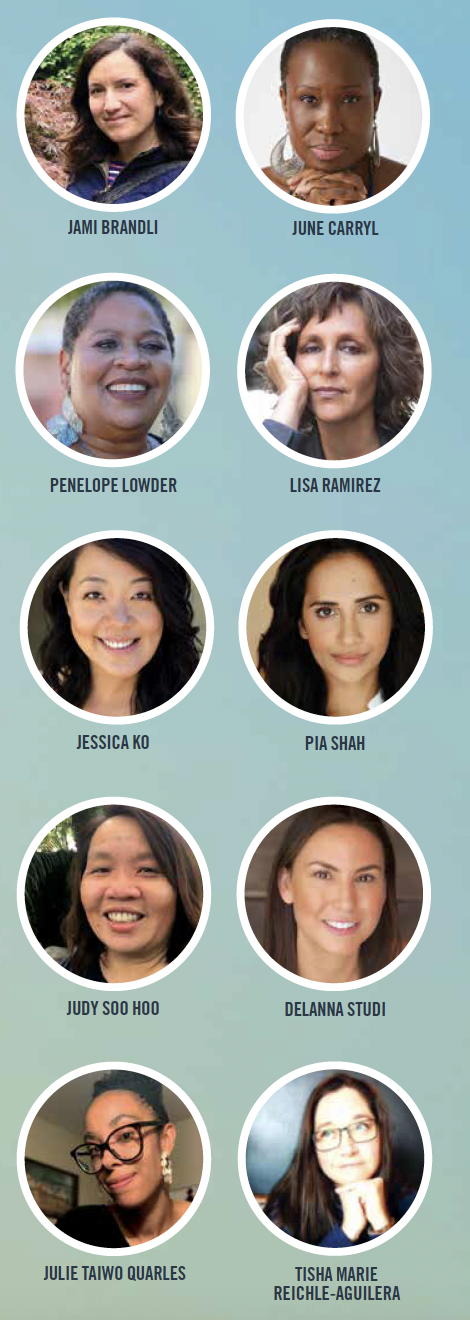

Get to Know the Writers

JAMI BRANDLI wants to know if you can name a female magician. Not an assistant, but a magician. She’s fairly certain you can’t. But after her play, The Magician’s Sister, you will. The play follows the story of two sisters, one of whom is a struggling female magician, interspersed with the stories of real, historical female magicians. And the play will incorporate many magic tricks.

Brandli grew up listening to stories at her parents’ restaurant. From then on, she knew she wanted to be a writer. She dabbled in fiction before returning to her “first love” of playwriting. She tells her graduate students to nurture their relationship to writing as they would with another person. “Writing is a marriage,” she said. “There will be really bad times and you have to stick with it...if you put in the effort and tend to the relationship, it will pay off.”

She hopes that “the individual stories I write are universally accepted and processed in a way that makes us feel more human together.” She challenges herself to write about different subject matters in all of her work, but if she does return to a subject matter (for instance, familial ties and units), she’ll explore it from a different angle.

JUNE CARRYL did not always want to be a playwright; she was supposed to become a lawyer.

“I discovered that as much as I love the law, the law is not necessarily about the truth, but rather about who wins,” she said. “As being someone with a need for absolutes, I was like, ‘I can’t live my life like that.’” As a playwright, Carryl is drawn to the intersections of race, gender, and ethnicity. Her play, Girl Blue, explores the mind of artist and activist Nina Simone. “The United States is a really great concept that fails miserably on a daily basis.

The experience of being Black and a woman epitomizes that failure or conundrum,” Carryl said. “I’m fascinated by the idea of Black women trying to find their place in a language that does not and cannot conceive of us as anything but Other... so it’s very subversive, just opening your mouth as a woman of color because you’re using words that were never meant for you.”

JUDY SOO HOO’s play, currently titled What Lies Behind the Tree, is about a woman’s journey to find her lost sister while also caring for her elderly father. “I’m working with memory. I’m working with the idea of grief and loss. Violence against women, aging parents. [And] how do you heal through tragedy and trauma?”

She asks audiences of her play to reflect on, “How does one work through trauma and embrace it? How do you walk through it? Even though the scars will linger? How do you walk through it? [And] with grace?”

Despite the serious subject matter, her playwriting is, literally, rooted in play. “As a child, I would hear the characters talking in my head and also ‘play act’ them out with my stuffed animals,” she said. “So, I really enjoy [writing], it is something I am loving and working and playing in.”

JESSICA KO returned to Los Angeles due to the pandemic lockdown cancelling every acting job she had scheduled in the next year, and was looking for new ways to get creative. Despite having never read her writing but knowing her work as an actress during their time together at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Alfaro invited her to the Writers’ Workshop because he knew that she may have “stories of [her] own to tell.”

Her untitled project is a fantastical tale about a woman who, upon receiving her grandmother’s ashes in the mail, must contend with the literal ghost of her newly awakened ancestor, and ultimately her family’s legacy. Ko said, “It takes inspiration from real life family anecdotes and Korean folk tales. It’s also an exploration about loss and grief, being a child of immigrants, keeping connected to family and constantly readjusting to those shifting identities of being wholly American and wholly Korean, which then creates the wholly unique identity of being a Korean American….It’s about finding your home and what that means, if it’s a place or city or with people or with yourself, or a combination of all of the above, whatever the alchemy of that is.” The L.A. Writers’ Workshop has empowered Ko to “officially call [herself] a playwright,” rather just “an actress who also writes.”

“Even in writing about moments of deep pain and trauma, I tend to find the absurd and humor in them too,” Ko said. “I suppose it’s my way of coping and processing life. And hopefully whoever reads or sees my work can also identify with that.”

PENELOPE LOWDER wants her audiences to “step into the shoes of people who have been traumatized by oppression.” As a writer, she initially gravitated toward writing stories about relationships. But now, she hopes to “decode the human condition,” often writing about race and relationships during the Jim Crow period, and the “spooky, supernatural elements” around it.

Her play, Barbara George, is “a 90-minute nightmare” that the titular Crenshaw realtor cannot wake up from. “She’s got to figure out how she can stay visible in a community where she is slowly being erased,” Lowder said. Lowder finds playwriting “difficult, but fun.” “I really love writing...because I can sit and let my imagination run wild,” she said. “And, yes, you can do the same with acting, but with writing, it’s like you have control over a whole world.”

JULIE TAIWO QUARLES thought she needed a break from writing during the pandemic, but the L.A. Writers’ Workshop helped her realize that wasn’t what she needed. Quarles first studied creative writing at Pepperdine University, where she now teaches, thinking she wanted to be an editor. But after a screenwriting class, she was hooked on writing.

“How crazy is it? To be able to see people performing things that I’ve written and to hear them speaking these words,” she said. “I just thought it was so exciting.” Quarles hopes audiences leave her plays with a similar sense of excitement. She also wants audiences to consider cultural interactions in new lights after witnessing her work.

Her play Yoj ™ is about two couples debating the trademarking of African culture. She’s fascinated by the interactions between the West and Africa, particularly because her father is Nigerian and her mother is American. “My play is inspired by recent controversies, in which certain cultures or cultural items are taken by people who don’t belong to those cultures,” she said.

LISA RAMIREZ became a writer on a dare. V, the writer formerly known as Eve Ensler, challenged Ramirez to write about the stories she heard from women while nannying in New York City. V told Ramirez, “‘There’s a reason you’re hearing all these stories. If you don’t tell these stories, they may not get told,’” Ramirez recalled.

She had only planned to write that one play, focusing instead on acting and survival jobs, but continued to write additional plays about the stories she heard from women in various industries, even eventually tackling “the idea of the Great American Play, but with Central American women immigrants as the protagonists.” Politics and playwriting have always intersected for Ramirez. All Fall Down is no exception—it is a semi-autobiographical memory play that explores larger themes of addiction and internal racism.

TISHA MARIE REICHLE-AGUILERA did not consider herself a playwright until the L.A. Writers’ Workshop. But now she sees herself as one, as well as a flash fiction writer and educator. Reichle-Aguilera writes “almost exclusively about women of color and community.” Los Angeles, where she has lived her entire adult life, has often played a role in her fiction, the city itself acting as a character. Her play, Blind Thrust Fault, takes inspiration from the earthquake-prone city of Los Angeles and from her seventeen years of teaching at a high school before getting her PhD.

This piece is particularly timely after the pandemic, when the profession of teaching became even more challenging. “I really wanted this particular play to center [teachers and center the work that they do. It’s both about the camaraderie of women teachers, and how they deal with their own traumas, their own life issues, [but] have students’ issues that they’re dealing with [as well],” Reichle-Aguilera said. She asks, “How can a person exhibit compassion for someone in pain or someone struggling while dealing with their own struggles?”

PIA SHAH wants to “give voice to the things that are sometimes taboo to say out loud in our society.” She is currently writing an untitled project “about motherhood and childbirth, marriage, and porn addicts” for the upcoming L.A. Writers’ Workshop Festival. This isn’t her first time tackling some of these subjects. Her short film, The Shower, tackles the conflicting emotions of motherhood through the eyes of two friends at a breaking point at one of their baby showers. She also wrote a feature film that landed on Netflix about two women getting high and musing about life walking through Griffith Park.

She began as an actress, earning her M.F.A. from USC, where she coincidentally first met Alfaro. As a playwright, Shah is “always trying to make people feel like they’re not alone, or that they’re less alone than they think they are.”

DELANNA STUDI’s Cherokee heritage inspires her work. She uses “Cherokee circular storytelling” in all of her plays, and often focuses her writing on the experience of being a Cherokee person in the world today.

“We believe that all planes of existence exist at the same time, so it’s not uncommon for ancestors and future generations to be in the room with us, and for things that are not considered to be humans to have human elements,” she said. Studi writes about, “white privilege, murdered and missing Indigenous people, [and] reparation and repatriation.”

Her play for the L.A. Writers Workshop, “I” is for Invisible, tackles the stories of many murdered and missing Indigenous and Native women as well as a new Oklahoma law that has restored reservation jurisdiction to native tribes.

“My pieces deal with historical and intergenerational trauma, but also resiliency and hope,” she said.

THE WRITERS

COMING SOON

SEPTEMBER 9 – 18, 2022

FESTIVAL TICKETS

FESTIVAL PASS

Enjoy all 10 readings for the price of $30!

Schedule

| Week 1 | |

| Fri, Sep 9 8pm | What Lies Behind by Judy Soo Hoo |

| Sat, Sep 10 4pm | Barbara George by Penelope Lowder |

| Sat, Sep 10 8pm | Sifting Through Ashes In A Zen Garden…But That’s Japanese Not Korean, So Never Mind by Jessica Ko |

| Sun, Sep 11 4pm | Tear! by Pia Shah |

| Sun, Sep 11 8pm | All Fall Down by Lisa Ramirez |

| Week 2 | |

| Fri, Sep 16 8pm | Girl Blue by June Carryl |

| Sat, Sep 17 4pm | Blind Thrust Fault by Tisha Marie Reichle-Aguilera |

| Sat, Sep 17 8pm | Yoj™ by Julie Taiwo Quarles |

| Sun, Sep 18 4pm | ‘I’ is for Invisible by Delanna Studi |

| Sun, Sep 18 8pm | The Magician’s Sister by Jami Brandli |