The Consciousness of a Community and Beyond

Occasionally a work of art emerges that defines a cultural moment and points to its future. In 1978, audiences in the United States were privileged to see such a work: Zoot Suit, performed first in Los Angeles and nine months later on Broadway where theatre critic Jack Kroll described the play as a key event in the consciousness of a community.

With the benefit of hindsight, we would add, in the consciousness of the broader community we call world culture.

Luis Valdez, writer and director of Zoot Suit, speaks to this point when he says, I wrote Zoot Suit for an American audience,

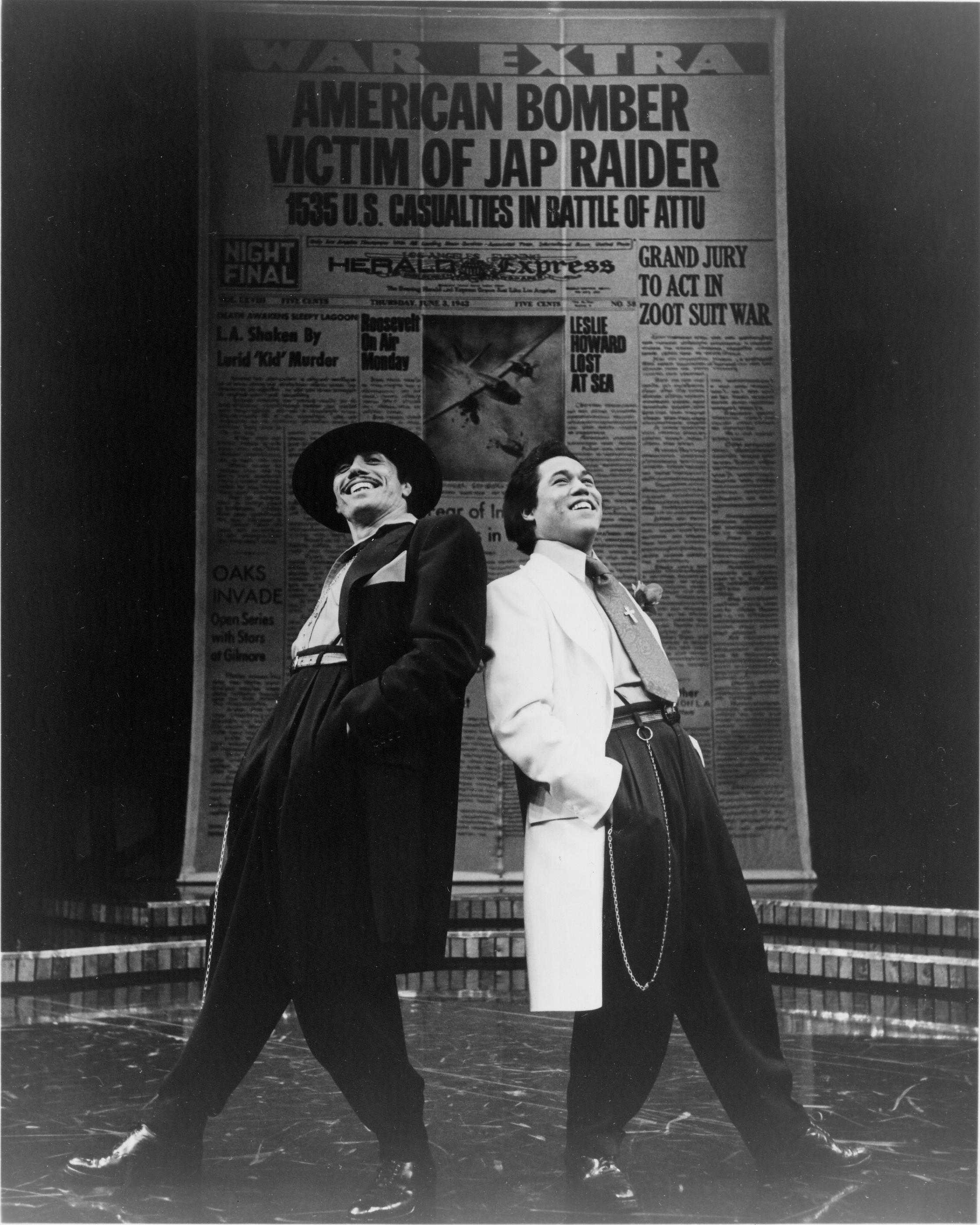

by which he means that the lives he is depicting should resonate beyond Chicano experience. When El Pachuco literally breaks through a giant newspaper to bound onto the stage in his black hat with its jaunty red feather, he is not only a man who wears a zoot suit of the 1940s. He is tempter, storyteller, shadow self, Aztec god, Mephistophelian devil, the embodiment of the conflicts of the play, the one who defines the play for us as real and stylized, historical fact and myth. The character refuses to be limited to any one definition; his identities are multiple.

Zoot Suit is a milestone in the artistic dialogue of the last quarter of the 20th century because it lays claim to an unbounded theatre that gets its juices from a particular identity but reaches beyond that identity. To this day, the play implicitly poses questions that continue to define our era: to whom does an artist speak, from what community, and beyond?

Before 'Zoot Suit'

Even before Zoot Suit, Luis Valdez had established himself as the leading force in Chicano theatre. The son of migrant farmworkers, Valdez first realized his vision of a Chicano theatre in the fields of Delano, California. Founded in 1965 as the cultural arm of the United Farm Workers, El Teatro Campesino began its life by performing on flatbed trucks in the middle of the fields, its actors, subject matter, and audiences all drawn from the workers who were fighting for better conditions.

It was a theatre meant to inspire, and it did. By giving back life experience transformed by humor and satire, the Teatro provided the replenishment and encouragement that the striking workers needed. By laying claim to the truth that theatre could be made from one’s own life, the Teatro spoke to students and community groups who began a national movement. By the mid-1970s, close to 100 teatros were performing in the southwestern United States, addressing a broad range of Chicano political and social concerns. In this new century, we in the United States heard the ongoing life of that inspiration when Barack Obama adopted Yes, we can

as his slogan, consciously using the motto of the United Farm Workers, Sí, se puede.

'Zoot Suit'

The play is based on the Sleepy Lagoon Murder, the name that newspapers and radio commentators used to describe the murder of José Diaz, whose body was found at the Sleepy Lagoon reservoir in southeast Los Angeles, California, on August 2, 1942. The murder led to the criminal trial and conviction of 21 Latino young men. While the decision was later reversed on appeal, the trial itself lacked the rudiments of due process. The episode was seen as the precursor to the Zoot Suit Riots a year later when U.S. sailors and marines roamed the streets of Los Angeles, savagely attacking anyone wearing a zoot suit, that emblem of urban bravado mixed with extravagant style. More than 600 Latino youths were arrested.

It is a horrifying story of virulent racism. It is also the story of a human being, Henry Reyna, the protagonist of Zoot Suit, his face brimming with hope at the beginning of the play, the wide smile of Daniel Valdez (Luis’ brother, who played Henry in the original production) lighting up his working-class family even as they bemoan his decision to enter the Navy. By the end of the play, we have seen that face disfigured by beatings, transfigured by love, defeated by demons, both outer and inner, matured and saddened by grim determination, even as his future is still in question.

It is Luis Valdez’s triumph both to give us a person whose fate matters to us as we watch his tragedy unfold, and also to create a new merger of naturalistic with expressionistic theatre so that Henry’s plight cannot be reduced to the story of one man. From the opening barrio dance it is clear that the inclusive stylization speaks to a new generation, for there among the Chicano youth is the Japanese-American dancer, Manchuka, and Swabbie, an American (presumably Anglo) sailor. El Pachuco extends the reach to African-Americans, singing, The Hepcats up in Harlem wear that drape shape/Como los pachucones down in L.A.

Nothing like this had been seen on the American stage: an outpouring of energy, inventiveness, of tragedy mixed with comedy, of the Brechtian European tradition put into the bodies of urban street kids.

One defining moment is the encounter between Henry and El Pachuco when Henry is already in jail. Go into the barrio of the mind,

El Pachuco whispers in his ear, forget the barrio, forget the family,

offering the temptation of oblivion, of drugs. Henry speaks back to El Pachuco in what is far more than a simple rejection of temptation. He undergoes a series of dawning revelations: what begins as an accusation (You’re the one who got me here

) becomes an acknowledgment of self: You’re my worst enemy, best friend. Myself.

Until this point, opposites have dominated the play as outward manifestations; when Henry is about to enlist, he is told, Forget the war overseas; yours is on the home front.

Now the audience feels that the play is also serving the inner life, that Henry will no longer feel torn apart but rather, in the Walt Whitman sense, he will know that he contains multitudes.

The towering strength of the play is that it does not try to reconcile opposites but rather to admit them into a range of possibilities, perhaps most obviously so in its variant endings. There is the official

tragic ending, in which an imprisoned Henry becomes a killer himself. Then there is another possibility: Henry is killed in the Korean War. Or he marries his sweetheart and raises his family in Los Angeles. Or…?

There are no answers and no inevitable future. These are possibilities that belong to all of us, existential choices and life trajectories that are real and possible, all part of the layered life of the play.

'Zoot Suit' and Theatre in the Americas

Theatre in the United States has always sought its distinctive voice, one that defined it as separate from its European theatrical inheritance. What does it mean, that elusive notion of an American theatre?

This was a question posed by Clifford Odets and Arthur Miller in mid-century America, answered through the prism of immigration, class, and the dangers of McCarthyism.

What does it mean to speak of the American experience? Or experiences? This is a question posed in the '60s and the '70s, when distinctiveness was emerging from the nation’s diversity, and racial, ethnic, and gendered groups put forth the claims of separate identities. In the '70s and '80s, previously unheard voices emerged, all challenging the narrow definitions of what theatre could be. Along with the development of Chicano theatre, African-American, Caribbean, feminist, and Asian-American artists were all entering into a productive fray, creating work that was shaped by the challenge of finding new artistic ways of representing identity.

In the work of Luis Valdez, we see something different: an explicit tension between community and the broader world. Valdez’s work presents a plurality of voices and points of entry that Valdez says is the American experience. That definition is why Valdez is especially pertinent to our time now. As Valdez put it in a 1988 interview in American Theatre magazine: I feel that the whole question of the human enterprise is up for grabs.

The question posed by Zoot Suit’s radical theatrical terms of 1978 is: what sort of alternatives exist in the United States, beyond racism and violence? Various possibilities are portrayed: the creation of an emblematic style such as that of the pachuco, heroic but self-destructive; the multi-ethnic composition of the defense committee that effectively worked with the families of the Chicano youth to win their appeal. Ultimately these possibilities are seen as insufficient to the immensity of the problem. Valdez again: I don’t think this country has come to terms with its racial question…and because of that, it has not really come to terms with the cultural question of what America is.

In the nearly four decades since Zoot Suit, much has changed, but the challenges it posed still stand, demanding a renewed vision of the United States and ultimately the Americas. The diversity of the United States and the connection among all the Americas are realities that can be ignored only through a willed blindness.

Have we begun to see a vision of a new multi-racial, multi-dimensional poetics? Yes, up to a point: influences between and among identities; the shedding of those identities entirely; the poking fun of old stereotypes and re-using them for a new mix; the new connections being forged between theatre in the United States and theatre of Central and South America. Zoot Suit continues to exert its pressure precisely because it articulated the vision; it walked the path between community and beyond, creating a trail that we are still on.

We dedicate this essay to Gordon Davidson (1933–2016), who nurtured Zoot Suit every step of the way. —SDL and JS

© 2016 Steven Lavine and Janet Sternburg. This essay was originally commissioned by the U.S. Embassy, Mexico, as an introduction to the 2013 Spanish language version of Zoot Suit.

About the Authors

Steven D. Lavine and Janet Sternburg (husband and wife) have long worked at the forefront of cultural change.

Steven D. Lavine is president (1988 – present) of the California Institute of the Arts, where he has created opportunities for educating multidisciplinary artists in bachelors, masters, and doctorate degrees, as well as creating national models for the creation of new work through CalArts’ performance space, REDCAT, and for the forging of new relationships among an arts college and its communities through the Community Arts Partnership. Lavine is also the co-author of Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display and Museums and Communities. He is proud to note that Luis Valdez served on the Board of Trustees at California Institute of the Arts from 1990–1996.

In 1970, Janet Sternburg, writer and photographer, discovered an unopened box at National Educational Television containing videos of early actos; these became the basis for her 1970 feature documentary El Teatro Campesino, broadcast nationally and shown at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. In 1980, W.W. Norton published her now-classic book The Writer On Her Work; Julia Alvarez, in her introduction to the 20th anniversary edition, wrote, "It was a first: seventeen women laying claim to rooms of their own in the mansion of literature." Sternburg is also the author of two books of memoirs, White Matter and Phantom Limb. A monograph of her photography, Overspilling World, has been published in 2016 by Distanz Verlag with a foreword by Wim Wenders.

Related Articles

"Zoot Suit"

Luis Valdez brings his groundbreaking 1978 smash back to the Mark Taper Forum January 31 – April 2, 2017, to celebrate Center Theatre Group’s 50th Anniversary.

Buy Tickets